1. Introduction

The sustainable integrated district planning approach helps to address economic challenges in two ways: (1) by promoting a self-sustaining urban ecosystem where people can live, work, and enjoy leisure activities within the same district, and (2) by focussing on the development and optimisation of specific economic functions within a city. This localised focus allows for tailored solutions that support the unique characteristics, challenges and needs of each district. One approach cities employ is fostering knowledge production in a well-governed urban space by strategically clustering innovative districts, educational institutions, and residential areas. This can lead to a skilled workforce, knowledge sharing, and innovation as businesses feed off each other’s ideas and advancements. Another strategy is to stimulate the production and consumption of amenities and services by co-locating consumer amenities and activities near one another. Sustainable integrated districts can be deliberately designed to be centres of such specialised activities and services. The presence of consumer amenities, like shopping centres, restaurants, cultural venues, and recreational facilities, plays a significant role in the decisions made by both businesses and households about where to locate. Businesses are attracted to areas where their employees can enjoy a high quality of life, while residents seek neighbourhoods that offer convenience and a desirable lifestyle. Research has shown that areas with a concentration of consumer amenities tend to experience economic growth and attract investments. The growth can stem from increased consumer spending, job creation, and improved urban vitality.

The contribution of this work package is as follows:

The study investigates the mobility patterns of the specific socioeconomic groups using the economic context of the districts, measures mobility patterns and compares the “living room effects” that arose as the result of social interactions and the use of business and service spaces.

The study proposes an integrated framework for sensing the underlying hierarchical urban spatial structure of social hotspots, which benefits from both detailed human movement information and networks at a fine-grained scale and allows for a comparison of integration effects across districts.

2. Methodology

The case study one-north is compared to two control cases: Science Park I and II. Mobile phone locational data and datasets on various urban features, including points of interest (POI), were collected from different internet platforms and provided the basis for accessing economic performance in the selected sustainable integrated districts. A social interaction is defined as a serendipitous incident of at least two users being simultaneously in the same place within the respective district. Several measures of social hotspots and mobility patterns measures, such as Mobility Signature, were developed to assess the economic performance of sustainable integrated districts. The study employed spatiotemporal statistics and normalisation methods (1) to detect, measure and visualise mobility patterns, (2) profile Mobility Behaviour and social Hotspots and (3) investigate the “living room effect” that arises as the relationship between mobility and social hotspots in the districts. For instance, if a knowledge district has a more vibrant social hotspot than another, then its users are more mobile, and they also produce more social interactions and knowledge exchange, indicating a higher degree of spatial integration within a district. Suppose a consumer district has a higher share of non-local customers and a wider impact zone than another district with a similar predominant economic function; in that case, it borrows some of the agglomeration benefits of their neighbours while avoiding agglomeration costs, indicating a higher degree of spatial integration within the urban system.

3. Main Findings

The study of one-north SID uncovered a compelling set of findings: two smaller areas within one-north (also called subsites) —Fusionopolis and Biopolis—outperform Science Parks I and II in terms of intra-, inter-, and inner-zone spatial interaction patterns and ‘the living room effect.” These findings indicate the presence of more flexible zoning and vibrant street design for economic integration in these two business parks in one-north compared to the spatial structure of both science parks.

Figure 1 locates the Workplace Social Hotspots and demonstrates the spatiotemporal distributions. The observed hotspots are stable throughout the four workday periods in all three districts. The higher intensity of social activity is indicated in yellow and documented in Fusionopolis and Biopolis business parks.

Figure 1. Spatiotemporal distribution of social hotspots

Figure 1. Spatiotemporal distribution of social hotspots

Figure 2 maps the hierarchical networked spatial structure of social hotspots in terms of nodes that show the Betweenness Index as the node size; the node heat represents the zone-district connectivity, and the heat of the edges was used to visualise the actual traffic flows. Based on spatial interaction relatedness and hierarchical urban structure, the highest degree of the “living room effect” was observed in Fusionopolis and Biopolis.

Figure 2. Hierarchical networked spatial structure of social hotspots

1 Introduction

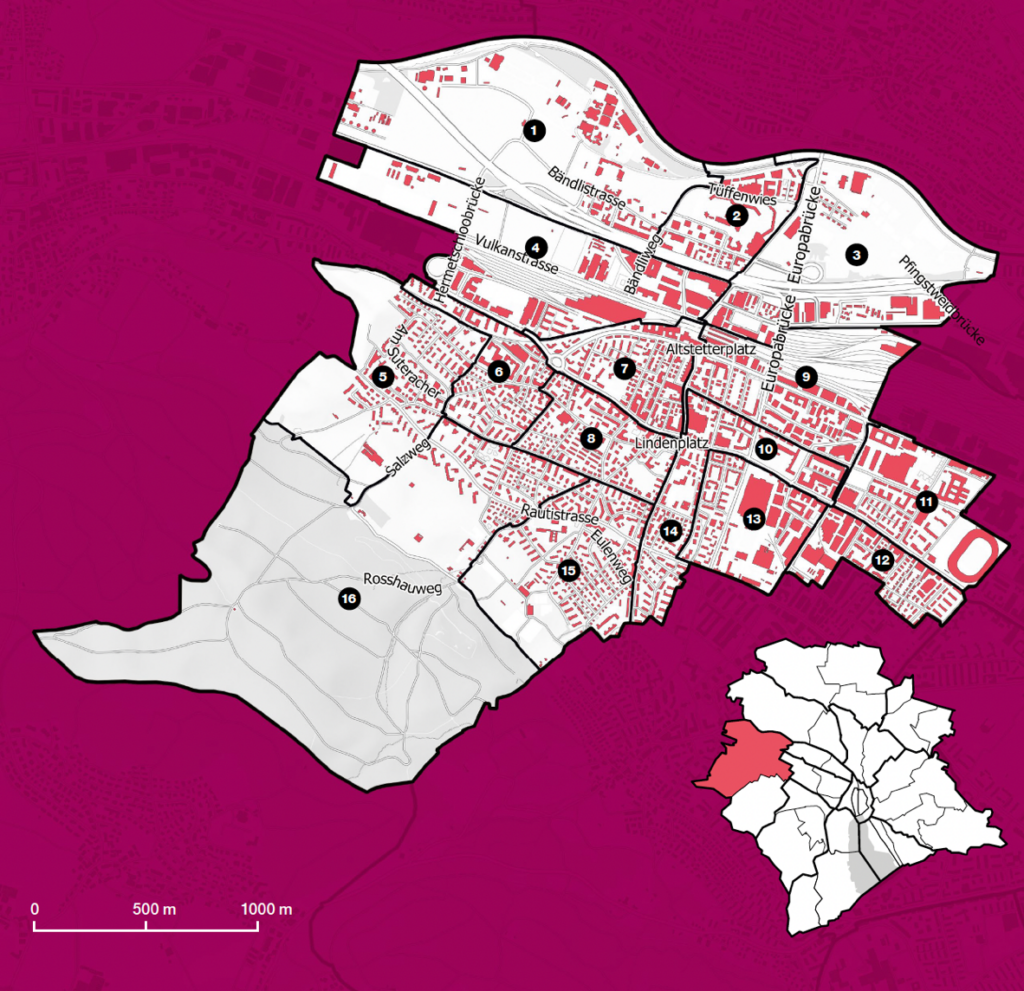

The district of Altstetten, in addition to the Oerlikon district, is one of the fastest-growing city areas (including residential growth and rising employment rates). Located in the western part of Zurich, the district covers 12.1 km2 and extends from the Limmat River to the Uetliberg Foothills (Figure 1). Following the predicted urban development scenario that Zurich’s population would increase by more than 20 per cent by 2040, Altstetten confronts the severe challenge of housing additional 13,000 residents (Stadt Zürich Statistik, 2023). Such growing urban population and, consequently, increased urban densification bring tremendous dynamics into the planning process and the ways of coordinating various and often conflicting interests of many urban stakeholders (e.g., authorities, landowners, residents), on the one hand, and a need for social inclusion while implementing the ‘green urban agenda’ principles, on the other.

Figure 1. The position of Altstetten within the urban area of Zurich. Source: Stadt Zürich Statistik, 2023

2 Aims

Given the previous challenges, this study is devoted to exploring the ways towards more resilient urban development using a two-fold approach. More precisely, the focus is not only on ‘what’ the essential features of green and dense cities are, but also on ‘how’ to achieve such urban development, inherently attending to the notions of cooperation, social inclusion and equity. Accordingly, the three main goals of the study are as follows. The study first aims to identify and structure a conceptual, analytical framework revolving around the principles relevant for dense and green cities. Then, narrowing down the scope to the case of Altstetten, the study explores the nature of cooperation in densifying practices. Finally, the study examines the extent to which ‘green urban agenda’ policy priorities have been implemented in practice, again focusing on Altstetten. Combining the research results with the findings of Space Use and Blue-Green Infrastructure sessions, the study offers a critical evaluation of the current policymaking, planning and design practice, pointing to the main lessons learnt as a direction for further action in the domain of green and dense cities.

3 Methods

The study applied a three-fold research strategy. The first step was to conduct a documentary analysis to identify the procedural principles, answering ‘how’ to achieve green and dense urban development, and the topical principles, answering the question ‘what’ the essential features of green and dense cities are. Using the method of content analysis, the study reflected upon the current and future urban development strategies addressing the topic of green and dense cities at three territorial levels: federal, regional and local (the city of Zurich).

Informed by the previous overview of procedural principles of green and dense urban development, the next step focused on the local level with the aim to select three case studies in Altstetten that showcase diverse levels of cooperation among numerous stakeholders (Figure 2):

- Koch Areal: with extensive dynamics among various interested parties

- Tüffenwies School Area: considered the first genuinely participatory urban development in contemporary Zurich, with the crucial role of planners as facilitators of cooperation

- HdM project: as an example of the pro-development approach, yet with controlled gentrification

Figure 2. The position of three selected cases within the neighbourhood of Altstetten. Source: Perić et al. 2023

The study applied the method of qualitative in-depth analysis and interpreted relevant information and documents, such as newspaper articles from the Zurich daily press (i.e., Tages Anzeiger and Neue Zürcher Zeitung); interviews with diverse stakeholders, including developers, residents, planning professionals and city officials; and overviews of the projects’ archives. The courses of project development and the interrelations between stakeholders were illustrated through diagrams for further critical reflection upon the norm of cooperative planning, while the systematisation of findings revolved around the following variables: nature and extent of cooperation, major bottlenecks in achieving practical cooperation, the main allies and critical opponents, the ways of identifying compromise, and the main cooperative mechanisms undertaken.

The last step again focused on the local scale, attending to the topical (i.e., green agenda) principles, and the extent of their implementation in Altstetten. To achieve this, the study employed empirical research data and information from the sessions of Social Performance and Blue-Green Infrastructure, focusing on the cases of Grünau, Lindenplatz, Bachwiesen and Süsslerenanlage and their 400-metre radius surrounding areas.

4 Findings and outcomes

4.1 Procedural and topical principles of green and dense urban development in Switzerland

Documents | Cross-cutting PROCEDURAL principles | Cross-cutting TOPICAL principles |

Sustainable Development Strategy 2030 (Federal Council, 2021) |

|

|

Action Plan 2021-2023 for Sustainable Development Strategy 2030 (Federal Council, 2021) | ||

Megatrends and Spatial Development in Switzerland (ROR, 2019) |

|

|

Trends and Challenges: Figures and Background on the Swiss Spatial Strategy (ARE, 2018) |

|

|

Swiss Spatial Concept (Federal Council, 2012) |

|

|

Planning and Construction Law PBG (2013) (OS 68, 189; ABl 2011, 1161) |

| |

Spatial Planning Law RPG (2019) |

|

|

Cantonal Richtplan Zurich 2035 (Cantonal Council, 2019) |

| |

Long-term Spatial Development Strategy of Canton Zurich (Cantonal Council, 2014) |

|

|

Regional Richtplan (City of Zurich, 2017) |

| |

Communal Structural Plan (Stadt Zürich, Hochbaudepartement, Amt für Städtebau, 2021) |

| |

Strategies Zurich 2035 (Stadt Zürich, Stadtrat, 2016) |

|

|

Table 1 shows how procedural and topical principles addressing green and dense urban development are ingrained into various federal, regional, and local (city of Zurich) strategic and regulatory planning documents.

Table 1. Principles of the major federal, regional, and local (city of Zurich) urban development policy documents. Source: Ana Perić (unpublished material).

From the previous documentary analysis, it is indicative that the procedural principles are not elaborated in the Communal Structural Plan, i.e., a kind of master plan serving to transfer the main priorities defined at the higher administrations (federal, cantonal office) to the city level. However, the absence of procedural principles in the strategic framewoek does not necessarily mean that urban planning instruments lack cooperative aspects. Namely, the procedure of ‘cooperative planning’ is an informal planning instrument yet widely used as complementary to official planning tools. The procedure can be initiated either by landowners or public authorities (city), coordinated by the city planning office (and other relevant city departments), while other interested parties (developers, citizens) can be included. The planning instruments that rely upon the cooperative planning procedure are numerous and widely used in Swiss planning practice, like the test-planning process, feasibility studies, and competitions. The essence of cooperative planning is ingrained into these informal tools; however, the strong emphasis on cooperation can also be found in some formal planning instruments (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Overview of the formal and informal urban planning procedures and instruments in Zurich. Source: Perić et al., 2021

4.2 The nature of cooperation in densifying Zurich: the example of Alstetten

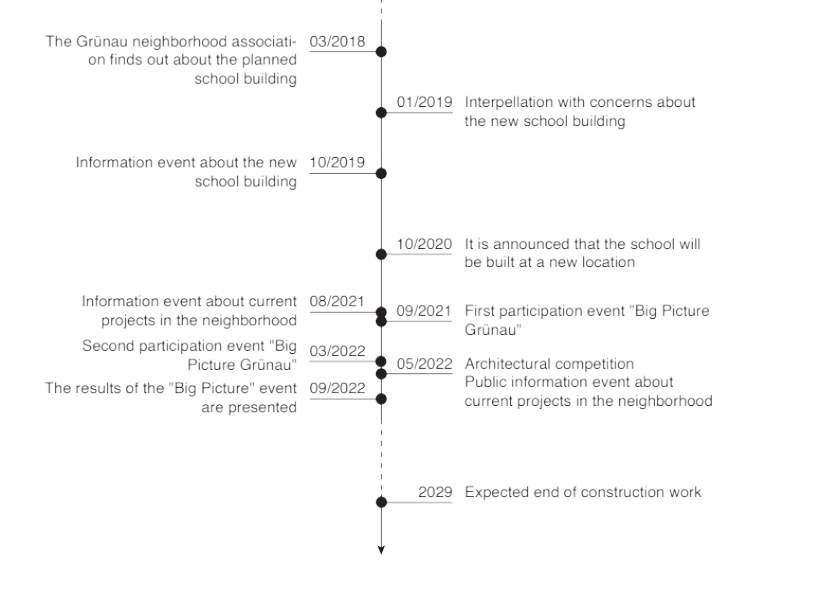

The timelines depicting the most important milestones as well as the stakeholder-networks and dominant narratives are illustrated in Figure 4a,b, Figure 5a,b and Figure 6a,b, referring to the cases of the Koch Areal, Tueffenwies and HdM, respectively.

Figure 4a. Koch Areal: the process timeline. Source: Perić et al. 2023

Figure 4b. Koch Areal: Stakeholders and the dominant narratives. Source: Perić et al. 2023

Figure 5a. Tueffenwies: the process timeline. Source: Perić et al. 2023

Figure 5b. Tueffenwies: Stakeholders and the dominant narratives. Source: Perić et al. 2023

Figure 6a. HdM: the process timeline. Source: Perić et al. 2023

Figure 6b. HdM: Stakeholders and the dominant narratives. Source: Perić et al. 2023

Testing the norm of cooperative planning on different case studies of the Alstetten district (Koch Areal, Tueffenwies, HdM) elucidates the fact that different types of collaborative practices have been applied to various extents in various projects. Although the essential exchange of facts and beliefs about the development initiatives was generally well achieved through a few instruments (exhibition events, round tables, site talks), information about the future densification projects was not always timely presented to the public (i.e., it happened after the agreements between the developers and city officials have been made). The sharing of knowledge, feedback and raising the level of mutual trust was most evident among the stakeholders with less uncertainty – mainly politicians as decision-makers, generally pro-development oriented, and developers – as the financial enablers of densification mechanisms, and where the need for greater public engagement was omitted, as seen in the HdM case. The greater use of formal planning tools and a range of statutory mechanisms, as well as increased coordination among the public bodies with continuous feedback between planners and decision-makers through a controlled private sector involvement, was depicted in the case of the Koch Areal. Nevertheless, all these webs of action did not seem to prove sufficient to protect the locals and their interests. Genuine collaboration is considered rare, except when planners, triggered by the citizens’ incentives, get to recognise existing power imbalances and, thus, actively support voices without financial or land resources, as evidenced in the case of Tueffenwies. Hence, collaborative governance is yet to evolve, on the one hand, backed by the direct democracy setting of Switzerland, but inevitably struggling under a globally pursued neoliberal urban development approach and a financialisation of densification.

4.3 The nature of ‘green urban agenda’ in densifying Zurich: the example of Alstetten-Albisrieden

The analysis of the core strategic and regulatory documents at the local (city of Zurich) level, through the lens of the ‘green urban agenda,’ demonstrated that the following principles respond directly to green spaces and their attributes: preservation of city nature, high-quality open public spaces, ‘Kurze Wege’ (short distances), garden city, and social inclusion coupled with natural preservation. These five principles can generally be grouped into three comprehensive groups. The first one covers the overall attitude towards natural environments; the second one covers the aspects related to the physical structure of green spaces, such as size, main ecological features, equipment, design, and connectivity. The last group emphasises the human aspect of the ‘green urban agenda,’ in other words, how green spaces are used and by whom, highlighting the balance between urban lifestyles and natural environments.

When empirically tested on the case of Altstetten, i.e., four clusters of Grünau, Lindenplatz, Bachwiesen and Süsslerenanlage and their 400-metre radius surrounding areas (as informed by the results done within Social Performance and Blue-Green Infrastructure sessions), the following findings were devised:

- Preservation of city nature: This implementation of this principle is starkly evidenced in the entire district of Altstetten. In addition to the geographic borders of the Uetliberg Hill and the Limmat River, the proximity of natural environments to urban areas is a secure way to protect biodiversity and ecosystem services. Bachwiesenpark represents an excellent counterbalance to the densely built residential area of Freilager. Many activities in observed green clusters indicate the generally strong bond of people to the natural environments.

- High-quality open public spaces: The four cluster green spaces indicate a wide variety of green areas within the observation perimeter. Public green spaces and community green spaces providing accessible and well-designed areas encourage diverse types of activities, as demonstrated by the observed activities in terms of both frequency and duration. Furthermore, the observation results suggest better equipping public and community green spaces with the appropriate facilities and surfaces to fulfil different outdoor activities.

- ‘Kurze Wege’ (short distances): The entire district area successfully implements the ‘short distances’ and ‘green corridors’ principles. It is particularly evident in the central district’s area, with the highest connectivity rate among various green areas. City parks and other public green spaces are strategically distributed across the district, ensuring that residents can reach at least one such space within a ten-minute walking distance.

- Garden city: The district of Altstetten and Albisrieden was designed as part of the ‘Garden City’ concept in Greater Zurich in the 1930s, and this concept is still evident from the perspectives of green space provision and allocation among the dweller population in general. However, the disconnect between space significance in the urban fabric and the space size indicates the reason for the unbalanced use frequency crossing the district. It also suggests that a well-thought-out plan considering the size and location of green spaces within the urban structure is essential to fully utilise their potential.

- Social inclusion coupled with natural preservation: Social equity and cultural diversity across observed green space clusters vary. This variation results from the combination of space-use activity diversity and atmosphere supported by the green space organisation, property boundary design, facilities installation, and local community values. Such factors interacting with each other contribute to the balance between urban lifestyles and natural environments to various extents.

5 Recommendations for urban planning and governance

Looking through the lens of procedural principles of green and dense cities and their implementation in planning practice in Zurich, the following findings are devised. Cooperative planning as a procedural norm in Zurich’s planning practice has yet to evolve through inducing more intrinsically bottom-up approaches aimed at broader community engagement. The analysed cases show that social equity, inclusion and spatial justice are still challenging to implement, even in the Swiss direct democracy setting. With a global strengthening of the neoliberal development paradigm, countering social displacement and exclusion is not expected to be prioritised within the political agenda. Nevertheless, even when profit is not an ultimate planning outcome, the nature of planning fails to be genuinely cooperative, revealing politicians as the weakest links in ensuring securing the active involvement of the least powerful parties – ordinary citizens. Therefore, from the professional perspective and taking the stand that planning is inherently embedded into a socio-spatial setting, approaches such as transformative planning – planning for and with people – may help planners to listen to what is happening on the ground with the very locals and not forget the very essence of their profession as the way not to be lost in many challenges of contemporary urban development.

Observed from the perspective of topical principles of green and dense cities and their implementation in planning practice in Zurich, the findings reveal that most policy objectives – preservation of city nature, high-quality open public spaces, good connectivity, and high average green space area per resident – are implemented to a high extent in practice. However, more intangible attributes of green spaces, such as social equity and cultural diversity, are yet to advance to fully increase social inclusion in green spaces. Namely, despite the abundance of community gardens, which by their definition should serve all the community members, it is very difficult to achieve meaningful interaction between groups with various cultural, language, and ethnic backgrounds. Furthermore, while green spaces and associated facilities are provided in the district, a careful consideration of location, size, and the role of green spaces in the broader urban context would be essential to ensure an effective application of the principles. Finally, an in-depth understanding of the local community, including the recognition of various local users’ needs and of other potential users will improve the access, use, quality, and social inclusion benefits of green spaces. Such an approach can ultimately increase awareness about the natural environment among urban dwellers.

6 Relevant Publications

- Jiang, Y., Menz, S. & Peric, A. (2023). Urban Greenery as a Tool to Enhance Social Integration? A Case Study of Alstetten-Albisrieden, Zurich. In Y-F. Yang (Ed.), Sustainable Built Environment (forthcoming). London: IntechOpen, DOI: 10.5772/intechopen.109736.

- Jiang, Y., Menz, S., Peric, A. & Guariento, N. (2022). From Green Continuity to Social Integration: A Case Study on the Social Potential of Urban Greenery in Altstetten-Albisrieden, Zurich. In Z. Enlil, E. Belpaire, R. Schuett & S. Morgado (Eds.), In Search of a New Planning Agenda for Urban Health, Socio-Spatial Justice and Climate Resilience (Proceedings of the 58th ISOCARP World Planning Congress) (pp. 1094-1109). The Hague: ISOCARP.

- Peric, A., De Blust, S., Jiang, Y., Guariento, N. & Wälty, S. (2022). Urban Strategies for Dense and Green Zurich: From Healthy Neighbourhoods towards Healthy Communities? In Z. Enlil, E. Belpaire, R. Schuett & S. Morgado (Eds.), In Search of a New Planning Agenda for Urban Health, Socio-Spatial Justice and Climate Resilience (Proceedings of the 58th ISOCARP World Planning Congress) (pp. 1654-1667). The Hague: ISOCARP.

- Peric, A., Hauller, S. & Kaufmann, D. (2023). Cooperative planning under pro-development urban agenda? A collage of densification practices in Zurich, Switzerland. Habitat International, 140, 102922, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2023.102922.

- Peric, A., Jiang, Y., Menz, S. & Ricci, L. (2023). Green Cities: Utopia or Reality? Evidence from Zurich, Switzerland. Sustainability, 15(15), 12079, https://doi.org/10.3390/su151512079.

Research Team